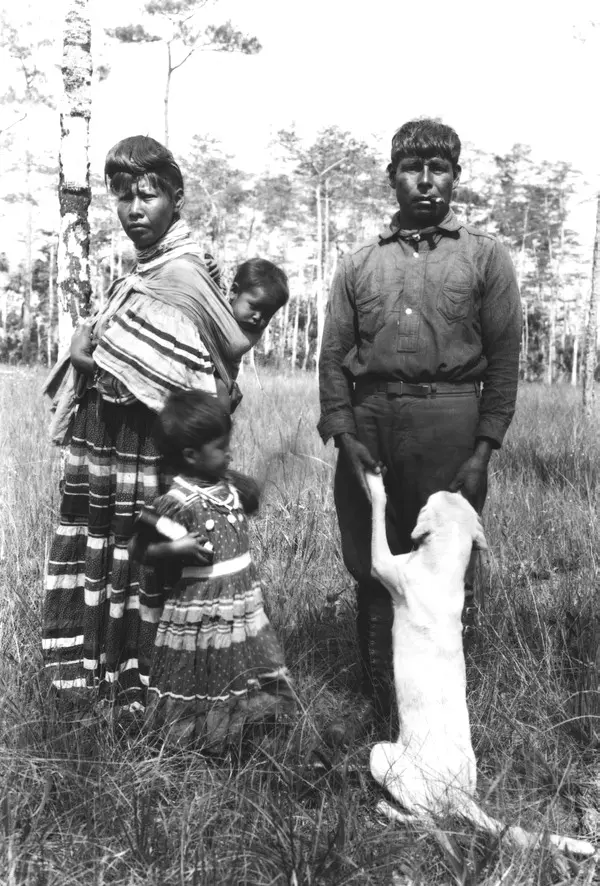

Florida’s early American Indians

We are approaching the 500th anniversary of what, just a few years ago, would have been called the “discovery of Florida” by Juan Ponce de Leon. Most historians now agree that Ponce de Leon was not the first European – or even Spaniard – to set foot on Florida soil, though they disagree on who made that first step or when it may have occurred. What isn’t in dispute is that none of them were truly the first to tread upon the sands of Florida.

Twelve thousand years ago, Paleoindians, continuing their southern migration through the North American continent, entered the peninsula of Florida. These “First Floridians” encountered many different plant and animal species, including some that are now extinct – such as mastodons, mammoths, giant sloths, and saber-toothed tigers. Over time, these people developed a sedentary lifestyle. With this lifestyle came a more complex culture, evincing itself into separate groups among the natives of Florida.

The two largest native groups were the Timucua and the Calusa. The Timucua, a loose alliance of many tribes sharing the same language and traditions, encompassed much of north Florida, while the Calusa, or Calusa-related tribes, controlled much of southern Florida. A number of smaller groups called the Tampa Bay area home.

The Mocoso lived on Hillsborough Bay between the Hillsborough River and the Alafia River. Their territory included what is now downtown Tampa. The Tocobaga, numbering about 1,300, lived along the northern part of Old Tampa Bay. Their main village was in the Safety Harbor area. The name Tampa may be a corruption of the name of the Tocobaga town Tanpa, as recorded by Hernando d’Escalante Fontaneda, the survivor of a Spanish shipwreck. The Pohoy also lived around Old Tampa Bay. The name first given to Tampa Bay, possibly by the Spanish, was the Bay of Pohoy.

The Uzita (Ucita) were a larger group living in the area from the mouth of the Little Manatee River south to Sarasota Bay and as far inland as Parrish.

Timucua social organization, like most other native groups, was centered on clan affiliation. The clan was far more important than the town or village in which one lived. Clan membership was matrilineal, although village leaders were always men whose position of prominence was decided by clan affiliation. The Spanish called the native leaders caciques, the Arawakan word for “chief” common in the Caribbean. The Timucua word, however, is holata or parucusi. Spanish priests documented the Timucua language during their missionary efforts to convert the natives.

Early European explorers described the Timucua as muscular and well-proportioned. Timucua men, who stood approximately five feet nine inches tall, dressed in breechcloths and sometimes wore dyed deerskins decorated with images of wild animals. Women’s attire consisted of Spanish moss or deerskins draped over the shoulder or wrapped around the waist down to the thigh.

Timucua women arranged their hair loosely about the shoulders. The men wore theirs in tall topknots, sometimes decorating them with plant fibers or brightly colored feathers. Men probably favored this style because it made them appear tall and fearsome in battle. The topknot style also allowed freedom while going about their daily tasks. Prominent men tattooed themselves by incising their skin and rubbing soot or powdered charcoal in the deep scratches. When healed, the tattoo took on a bluish hue.

Inflated fish bladders hung from the pierced ears of the males. Both men and women wore ornaments made of polished stones, shells, bones, and animal tails, about their necks, waists, knees, and ankles.

The Calusa, like the Timucua, utilized the Gulf of Mexico for their supply of food. Considered non-agricultural, they lived principally on shellfish, which abounded in regions like the shallow waters among the Ten Thousand Islands off the southern coast of Collier County. They used bows and arrows, spears, atlatls, both with stone projectile points and made many tools and ornaments of bone and shell.

The Calusa were rivals of the Timucua and claimed a large territory – from about modern Manatee County to the Keys and inland to the center of the peninsula. The heart of the Calusa territory was centered on Charlotte Harbor south to Naples.

These coastal dwellers were accomplished seamen who adapted their sailing vessels to carry them as far away as the Caribbean. This is evidenced by trade items that have been found in archaeological sites.

Archaeologists believe that the Calusa even fished at night, using clay-lined fire pits in their canoes.

The Timucua and the Calusa frequently fought over territory, and it is likely that the area between the northern coast of Tampa Bay and Manatee County was disputed land.

Village life for the Calusa was much the same as it was for their north Florida counterparts. Their homes were palm-thatched huts and their discarded shells became mounds. However, their life in a sub-tropical environment dictated that they make subtle changes. One such adaptation was keeping smudge fires beneath their sleeping benches to control insects.

Few Florida Indian tribes survived to 1700. Between 1685 and 1708, Yamassee and Creek Indians from the north (today, the states of Georgia and Alabama) and English colonists from Carolina staged devastating raids against the Timucua and Apalachee tribes of north Florida. The natives of Tampa Bay were decimated by European diseases such as measles, smallpox, and influenza, as well as, by warfare and slaving raids. By 1711, there were no organized Native towns in Florida except near St. Augustine, where the Castillo de San Marcos offered some protection from northern incursions.

In 1763, England took a twenty-year possession of Florida. Archaeological evidence discovered on the southern end of the Courtney Campbell Causeway leads scholars to believe Cuban fisherman and Tocobaga, who once prospered in the area, probably left for the Caribbean about that time.

This story was first published by the Tampa Tribune on March 17, 2013.