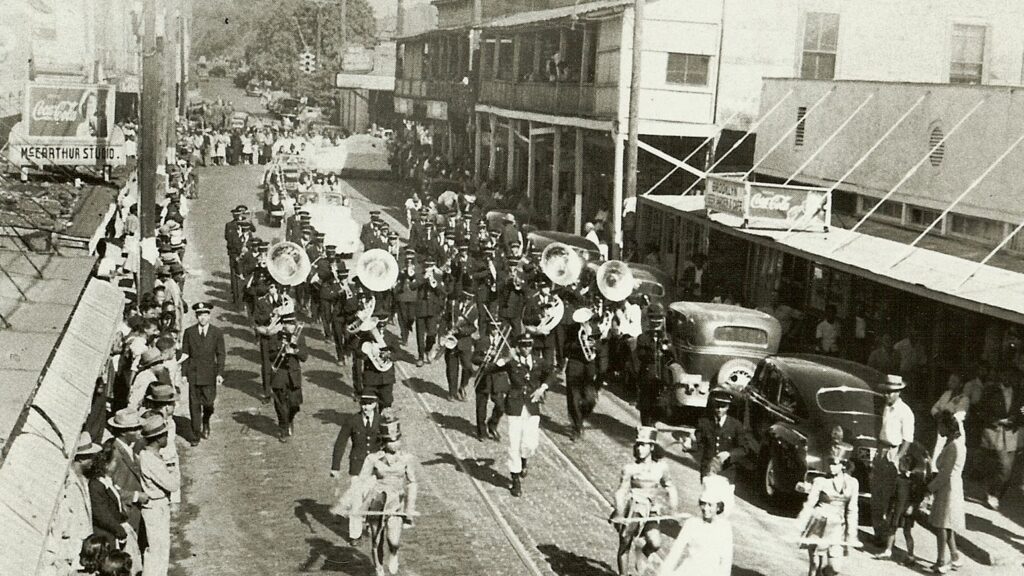

Black business district grew from the roots of segregation

Much has been written about the heyday of the Central Avenue business district, the main business and recreation center for Tampa’s African American community through the 1960s. The story of how Central Avenue came to be the center of black life in Tampa – and what came before it – has not received as much attention, but it is an interesting story nonetheless.

The Central Avenue business district sat at the western edge of The Scrub, which was Tampa’s first African-American neighborhood. Tracing its lineage to just after the Civil War, The Scrub was settled by formerly enslaved people and freemen from the area who, during Reconstruction, experienced a small but meaningful amount of freedom and economic success. With the end of Reconstruction in the early 1870s came an end to that success, while at the same time, Tampa in general, continued its slow economic decline.

Prosperity came to Tampa in 1883 in the form of a steam engine; Henry Plant’s railroad, along with his steamship line, immediately transformed Tampa. Combined with the introduction of the cigar industry in 1885, Tampa enjoyed a population boom. Though consisting largely of Cubans in the beginning, that population growth crossed demographic lines and included southern-born whites and blacks. Many African Americans who moved to Tampa found homes in The Scrub, which was becoming less isolated as downtown began growing toward its western edge and the establishment of Ybor City just to the east.

Tampa, at this time, was mostly confined to what is now downtown south of the interstate. Most of the growth, particularly among white businesses, was centered along Franklin Street south of Twiggs Street. This left a void north of Twiggs that was filled, to some degree, by the few black-owned businesses and professional offices that existed.

The 1886 Tampa city directory is among the earliest sources that detail most of the household and business addresses in the city. The majority of African American listings, designated by the use of an asterisk, are for residences and do not include an occupation. Many of those residents do not have specific street addresses but are instead listed as living in The Scrub. None are listed as living or having businesses on Central Avenue, which itself had a different name – Center Avenue. Given its relationship between old Tampa and new Ybor City, it is possible that Central (or Center) Avenue was named because it sat in the center of the rapidly growing city.

In 1893, the city directory canvassers found a total of twenty-one African American businesses with a small handful located in The Scrub. Significantly, though, two businesses called Central Avenue home: a barber shop and a restaurant.

Just two years later, according to the 1895 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Tampa, seventeen black-owned businesses were located along Central Avenue, including three restaurants, three barber shops, three grocery stores, two butchers, a fruit stand, a shoemaker, and a carpenter. In addition, the adjacent streets – Scott, Constant, and Harrison, in particular – also began adding businesses. Still, at this time, Central Avenue and the surrounding neighborhood consisted mostly of small homes and boarding houses.

In 1899, the city directory shows fifty-six African American businesses, with nineteen on Central Avenue. In addition to the businesses that existed four years earlier, others opened up shop on the growing thoroughfare. Those included a physician, an upholsterer, a jeweler, and an undertaker.

The majority of black businesses, as in the past, were located on the northern edge of downtown Tampa. Polk Street held the most, but others could be found on Lafayette Street (today’s Kennedy Boulevard) and Franklin Street.

Also, by this time, Tampa’s black community was expanding past the limits of The Scrub, with African American homes and businesses in Ybor City, West Tampa, and the Town of Fort Brooke (on the site of the old military fort at the southeastern end of downtown, which gave the area its nickname – The Garrison).

Ten years into the 20th century, the business district around The Scrub continued to grow. The number of businesses on Central Avenue grew to twenty-four by 1910, out of a total of 139 black-owned businesses listed in that year’s city directory. The streets near Central – Scott, Constant, Polk, Harrison, and Pierce in particular – also saw an increase in the number of African American-owned and operated businesses and trades. By 1910 there were two black attorneys in Tampa, including one with an office on Central and nine physicians (two on Central). The Avenue also served as the address for Tampa’s first African American newspaper – The Florida Reporter.

Looking back, Tampa’s main African American business district could just as likely have grown up on the northern edge of downtown rather than to the east adjacent to The Scrub. This did not happen, though, mostly because of the expansion of white businesses and professional offices as well as the continued growth of Tampa Heights, which, too, was just north of downtown. Central Avenue soon attracted more businesses, and wood-frame homes were replaced by brick storefronts.

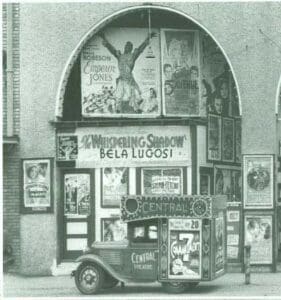

By 1915, Tampa was booming, and so was Central Avenue. Forty-eight businesses operated on Central between Cass and Scott Streets, while homes continued north along Central to Henderson Avenue in Tampa Heights (not to be confused with Henderson Boulevard in South Tampa), which was the invisible line between white and black Tampa in that neighborhood. Saloon keepers, tailors, a cigar manufacturer, a confectioner, grocers, and real estate agents could be found on Central, along with two movie theaters, a hotel, a notary public, a pharmacy, and six restaurants.

Central Avenue was coming into its own, and much of the growth came from business owners moving away from downtown Tampa to the African American downtown along Central. That trend continued throughout the 1910s, and by the early 1920s, Central Avenue was the center of black life in Tampa.

The Tampa Tribune originally published this article.